Wrath of the Ents by Ted Nasmith

By the time this post goes out the 2024 US Presidential Election will have (hopefully) wrapped up. The correct person will have been elected and our problems will soon be solved. Anxieties will simmer down. Everyone will accept the results and we’ll finally go back to peacefully living our lives.

If only.

No, I’m sure that this is just the start. I don’t see either side of the political aisle reacting well to their candidate’s defeat. Or rather, their opponent’s victory. Because now more than ever we’re voting against people more than we’re voting for them. Fear is hanging in thick clouds over the country and not without good reason.

But this is not a political Substack.

That’s not to say that I’m not a political person–after all, I will be voting–but my general rule is to delegate attention to where I have the most power. And a single vote cast into an ocean of hundreds of millions doesn’t even break the top 10 most important things to me.

Again, it’s not unimportant. I think everyone in America should get out and vote. But it’s my belief that politics flows downstream of culture, and culture flows down from our fundamental beliefs about the world and how it works.

That’s what I’m most concerned with. Change the root and change the fruit, as it were.

So today I want to take a look at something that’s been pushing further and further into my thoughts as of late and that is this notion of the Machine.

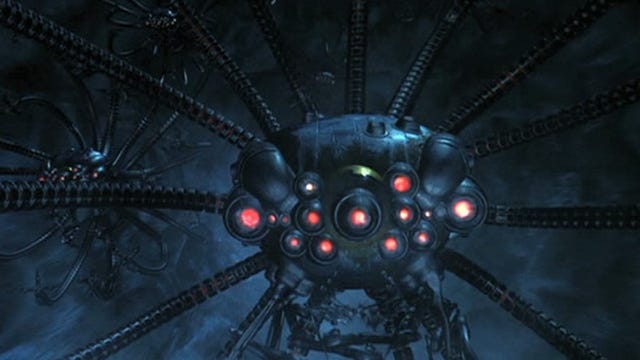

A sentinel from The Matrix (1999) Photo Credit: Warner Bros.

“We’re Building God, You Know”

In a guide to his essay series on the subject, writer Paul Kingsnorth describes the idea like this:

“The ultimate project of modernity, I have come believe, is to replace nature with technology, and to rebuild the world in purely human shape, the better to fulfill the most ancient human dream: to become gods. What I call the Machine is the nexus of power, wealth, ideology and technology that has emerged to make this happen.

In other words, the Machine is our modern world and our modern predilection for replacing the natural with the artificial.

In a shallow sense, this means cutting down forests and replacing them with strip malls. Or putting microchips in our heads or falling in love with AI chatbots. But it’s more than this. Those are symptoms of a greater disease. As Kingsnorth points out, the whole vision of the thing is to become like gods. To accept that offer in the Garden.

“For God knows that when you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

Genesis 3:5 NIV

If that sounds like a reach, consider the fact that the logo for the phones and computers half of the world uses is an apple with a bite out of it.

When speaking about her work on transhumanism, Elise Bohan had this to say:

“Is transhumanism encroaching on domains that religion has traditionally held? I think yes.”

Later on she describes an interaction with an enthusiastic biologist that went like this:

“Then he looked me in the eye and whispered to me: ‘We’re building God, you know,’ I looked back at him and I said: ‘Yeah, I know.’”

Or take this famous quote from Ray Kurzweil who was once the director of engineering at Google:

“Does God Exist? Well I would say, not yet.”

When thinking of Kurzweil, I’m reminded of this blistering comment Nassim Nicholas Taleb makes in his book, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder:

"I was just reading in John Gray’s wonderful The Immortalization Commission about attempts to use science, in a postreligious world, to achieve immortality. I felt some deep disgust—as would any ancient—at the efforts of the “singularity” thinkers (such as Ray Kurzweil) who believe in humans’ potential to live forever. Note that if I had to find the anti-me, the person with diametrically opposite ideas and lifestyle on the planet, it would be that Ray Kurzweil fellow. It is not just neomania. While I propose removing offensive elements from people’s diets (and lives), he works by adding, popping close to two hundred pills daily. Beyond that, these attempts at immortality leave me with deep moral revulsion.It is the same kind of deep internal disgust that takes hold of me when I see a rich eighty-two-year-old man surrounded with “babes,” twentysomething mistresses (often Russian or Ukrainian). I am not here to live forever, as a sick animal."

Sit with that for a moment. “I am not here to live forever, as a sick animal.”

But that is ultimately what transhumanism leads to: sick animals. An ideology that seeks to propel humanity towards some sort of transcendence VIA technology would have to lead there. After all, it’s the “animal” part of us that they take umbrage with.

Like Christians, they view the world as “fallen” but seek to fix the effects of that fall with technology. And on the face of it, this isn’t the worst idea. Modern medical technology has served to fill in the gaps of our physical brokenness in a countless number of borderline miraculous ways.

But there’s a difference between using medicine to live a full and meaningful life and using it to live forever.

The modern quest for immortality through means of technology is nothing more than the utopian quest through the very same means. Both abhor the natural world and seek to reshape it in the image of mankind. They have a vision for what the world should be as opposed to what it is.

And unlike other religions, there is no aspect of humility. Nothing transcendent to kneel before. When the goal is to push humanity into the realm of the gods then–like Kurzweil says–the only gods will be what we become.

So what’s wrong with this? What’s wrong with trying to become like gods?

In Genesis 2:17, God says:

“but you must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat from it you will certainly die."

Now we know from reading the rest of the chapter that Adam and Eve don’t die on the spot when they eat of the fruit. And we also know that this bit isn’t smoothed over, explained, or edited out. So we’re left to ask ourselves: What does it mean to die?

Biblically speaking, dying is more than just having your heart stop on the operating table. Dying is an act of uncreation. It’s the antithesis of “Let there be light.” Dying is a curse that infects the world and causes things to fall apart. The moment a soul leaves someone’s body they begin the long process of decay. When a nation loses its identity, it fragments and breaks down. When a band forgets why they started making music in the first place, they become something like zombies: shuffling forward through their careers but falling apart all-the-while.

And on and on and on.

Adam and Eve “die” because their identity was in God. Their place was in the Garden. Now they are cut off from the former and expelled from the latter. They are cast down into the thorns to toil for their food and shelter and things begin to fall apart. They have children but one kills the other. The murderer repents and builds the first city but eventually all of human civilization needs to be wiped away by a flood.

The falcon can no longer hear the falconer. Things fall apart.

So with respect to transhumanism and the machine, how do we die when we try to become “like gods?”

We die because we lose what makes us human in the first place. The Machine can’t stand all of those rough edges or idiosyncrasies. Ask any large corporation what it does with the eccentric employee whose work they don’t know how to quantify and convert to dollars: they fire them. Or at least push them to margins.

The Machine doesn’t like the animalistic nature of human beings. All of those unkempt desires and unexplainable habits rooted in the hazy mire of human evolution. It doesn’t like what it can’t quantify and commodify. If the human soul isn’t something that can be translated into binary code then it isn’t something worth saving.

In J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the Machine is represented by the totalizing power of the One Ring. It pushes us towards isolation and makes us feel cold and naked in the dark. We think we can use it just this once against the enemy but it’s the power itself that is the enemy.

Smeagol as he is corrupted by the power of the One Ring. Photo Credit: New Line Cinema

The Tower Will Fall

So how do we stop it? How do we throw the Ring into the fire, proverbially speaking?

In a recent talk, Paul Kingsnorth suggests “bringing the hammer down” on our devices and abstaining from the technological snare that we are increasingly building around ourselves. He admits that he doesn’t do this perfectly, a fact that is underlined by my reading of his Substack on a mobile device and listening to his interviews and talks online.

And that’s an important part to the conversation. I don’t think we need to throw all of our devices into the fire and burn down the server farms, as satisfying and liberating as that might be.

When the Israelites made their way out of Egypt and into the desert, they brought with them some unknown amount of Egyptian gold. Now this gold was intended for the development of the promised land once they arrived. However, much of it was instead melted down into the golden calf that so enraged God while he spoke to Moses up on the top of Mount Sinai.

And I think this speaks accurately to our relationship with technology. It can be a jewel in the walls of Jerusalem or an idol born of our disordered desires. We can use it wisely and with discernment or we can throw ourselves headlong into everything it promises, all while its serpentine body coils quietly around us.

In speaking about our development and use of AI, Paul Kingsnorth has expressed the worry that “something is using us to build itself.” A terrifying thought when expressed in that way. But it’s undeniable that we’re practically tripping over ourselves to put these things into actual physical bodies that can replace us.

When we build the Machine, we build a world unfit for humans. It must be said again and again, in attempting to transcend nature by the means of technology, we are eliminating nature. Or, more likely than not, setting ourselves up to be eliminated by nature.

Humans being used as batteries for the machines in The Matrix (1999) Photo Credit: Warner Bros.

And when I say “nature” here I’m not talking about birds and snails and sumac trees, though that is part of it. No, when I say “nature” what I mean is reality.

Reality abhors the Procrustean Bed of utopian states and artificial systems. The Tower of Babel will always fall. Those who seize the fruit in an effort to make themselves God will always be cursed to die.

Planting the Tree of Life

Until the time that the system comes violently apart, I think it’s important that we take a note from Tolkien here: don’t try to fight the Machine with the Machine. Don’t be like all of those AI developers who know what they’re doing is dangerous but feel compelled to do it because, after all, someone’s gonna do it so it might as well be them.

Instead, take regular and prolonged breaks from the internet. Don’t drown in the news. Don’t think that voting on the national level every four years is the only difference you can make in the world.

Take the time to read good books. Taste good wine. Have good conversations. Raise a family. Make friends with people who don’t believe what you believe. Go out and be “inefficient” in nature some time, banishing all thoughts of future ambitions for an afternoon while you watch insects move back and forth over a log or seek out the nest of that screech owl you hear every once and a while.

Be unpredictably generous. Love without limit. Or as Silent Planet’s Garrett Russel says: “Trade your certainty for awe.”

These are the things the Machine can’t understand. These are the tiny moments that short circuit the troll bots and grind down the gears of the Grind Set bros.

Live simply. Love fully. This is how you “plant the tree of life inside the heart of the machine.”

The Fall of Barad-Dur Photo Credit: New Line Cinema